Or, A Ramble About Craft.

I don’t pretend to have a “New! Improved!” perspective on writing, or any artistic expression, regardless of the medium, for that matter. I don’t have all the answers. I don’t have any answers, come to think of it.

I just have the moon outside my living room window. And a philosophy. It’s not even an opinion – those are like anal sphincters. Everyone has one. They pass some rather rank gases and other matter, too. No thanks.

Blind eye, writer’s block, deaf ear, clumsy hands. No matter what your chosen or preferred medium of artistic expression is, you’ve either heard these kinds of expressions before—or have experienced them firsthand. The composer who sits down to play, only to stare at the blank grids, and hear nothing in his mind. The writer’s Blinking Cursor of Doom, mocking. The painter who looks at the canvas and sees…nothing, not even negative space. Or the one who claims their mind doesn’t see in enough detail. Or what their hand does draw isn’t what they want it to be. Lost in translation.

It isn’t a lack of artistic inspiration that causes these things. It is the artist’s mindset, and approach. The inability to let go of the expectations of expression, of how you think the end result must look, feel, sound, taste, or what it should evoke. And let the artist in your hands do the work. Channel the vision, the concept, straight from your mind without amplification, filter or censure.

The concept is to render in a pure channel. Without the static that conscious thought and years of socio-cultural stigmas, preconceived notions and conventional thinking create. The definition of “render” in this sense is to depict, to translate.

Whether the medium is clay, metal, watercolor, acrylics, charcoal, graphite, ink, a camera or little round dots on black gridlines—or words—the artist is the sole interpreter. The only one capable of translating your vision into something that can be shared with the audience. Rarely is it the detail that conveys the concept—but the story of the whole. Not a single color or word, but the interaction of one with the next, the presentation of all, together, the composition, that shows the audience what the artist sees in their mind. The notes that make up the harmony of a song, the colors that blend to create the best hue. Or choosing the right words.

Are they important, those little pieces?

|

| The basic philosophy many artists forget. |

Of course they are. Without them, the whole would not exist. The translation cannot exist for the audience. But the whole will ever be greater than the sum of its parts. And so it is not the detail that the artist need be caught up in. But the scope. The landscape, the overall impact. Does it translate properly? The artist should not ask themselves, is it right? Instead, the question should be, is this what I see in my mind?

Writers often use real-life people—high-profile or otherwise—as inspiration for characters. What the character looks like to the reader may be completely different. Nothing wrong with that—it is not the writer’s goal to dictate how the reader sees, but to guide, and through that mold the concept. Otherwise, instead of offering descriptions, we would as writers simply insert the pictures, or names. Character X looks exactly like…Overpaid Blockbuster Actor Y.

Where is the artistry in that? There is none. Too much effort spent on the detail, on dictating exactly what the audience should see or what emotion they should experience…and the result is too controlling. Negates the engaging of the audience’s imagination. In attaining perfection of detail, the artist fails. Never mind the flaws. Flaws are what make the end result unique. Flaws are where the beauty is.

The idea, then, is for the artist to focus on the concept they wish to convey instead of getting lost in the details. Leave those to the audience to fill in for themselves, as no two will see the same ones. And that flexibility is an outlet for them to engage their own imagination and feed it.

That is what makes the book so much better than the movie.

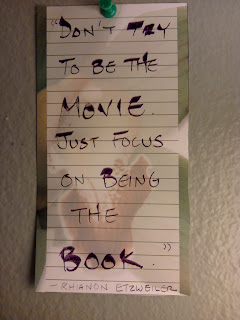

That's exactly it – we put so much pressure on ourselves to make some perfect down the last, minute detail that it becomes impossible to live up to that expectation. Besides, everyone knows the book is better than the movie nine times out of ten."Don't be the move. Just focus on being the book." Now there's a phrase that has come along just in time for me to throw myself back into this writing game.